Do you like historical fiction novels?

Do you like horror novels?

Do you like novels with a light touch of the fantastic?

Do you like novels written for teenagers that are far superior to many novels written for adults?

Do you like novels about the roles of women and men but especially women set in Victorian England?

Do you like novels about the history of science and scientific exploration?

Do you like murder mysteries?

Do you like prose that is as perfect as prose can be?

Do you like novels about girls who lie, who sneak around and keep secrets, who want revenge, who can be cruel, who constantly defy expectations and face danger and punishment for either being themselves or for being female to begin with?

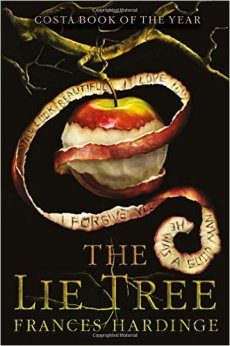

If you said yes to these questions, then you have no excuse not to read The Lie Tree.

Faith Sunderly is the shy, meek, obedient daughter of the respected reverend and natural scientist Reverend Erasmus Sunderly and his wife Myrtle, a fashionable society wife. Almost of age but with no beauty or social graces to speak of, Faith is an embarrassment to her mother and ignored by her father as nothing but a burdensome girl child. Faith shares her father’s passion for natural science and idolizes him deeply while yearning for the slightest sign of approval and acknowledgment of her cleverness from her grim, forbidding father.

There was a hunger in her, and girls were not supposed to be hungry. They were supposed to nibble sparingly when at the table, and their minds were supposed to be satisfied with a slim diet too. A few stale lessons from tired governesses, dull walks, unthinking pastimes. But it was not enough. All knowledge—any knowledge—called to Faith, and there was a delicious, poisonous pleasure in stealing it unseen.

After leaving their home in Kent with undue haste, the Sunderly family as arrived on the cold, rocky island of Vane, where Faith’s father has been invited to participate in a fossil excavation. Faith knows her parents are keeping secrets of why they’re on Vane—and as it turns out, these secrets are worth killing for. Faith’s father is discovered dead near the beach one morning. An accident, her mother claims. A suicide, the town whispers. A murder, Faith knows.

Vowing to uncover her father’s murder, Faith finds amongst her father’s possessions a rare, strange tree that only grows fruit when someone whispers a lie to it. In turn, the fruit will reveal hidden truths to the person who consumes it. Secrets and lies got her father killed, but they may also be the key for Faith to find her father’s murderer—if the lies don’t consume Faith first.

Wow. WOW.

Frances Hardinge is a stellar writer and an unsurpassable storyteller. I loved her earlier books Fly By Night and Fly Trap, and her last novel, Cuckoo Song, was one of my favorite reads of 2015. The Lie Tree is, without a doubt, the best novel of hers I’ve read yet. It’s sumptuously written and filled with uncomfortable, insidious, and ever-mounting tension and emotional horror. Like a scientific excavation, The Lie Tree plumbs the depths of closely-guarded secrets and half-truths surrounding the Sunderly family, Vane’s inhabitants, and the eponymous Lie Tree.

At the heart of The Lie Tree is just that—lies, and appearances, and the truth hidden underneath. Faith’s life is dictated entirely by lies masked as truth: young ladies must be good and pure of heart; young ladies are have little intellect and even less ability to withstand the rigours of science and learning; young ladies’ only worth lies in their virtue. Faith’s mother is a master of appearances—indeed, they’re the only weapons she has—and she uses her clothes, her speech, and her mannerisms to project the image of whatever woman she needs to be in order to gain an advantage. Faith’s father is a pillar of truth and a good man in the eyes of his loving daughter, but he carries dark secrets that throw into question his reputation and what kind of man he truly is. All three of them are at the mercy of society, the hat rack on which these lies are hung. These lies feed and validate society’s continued existence as a necessary institution dictating every person’s “true” identity, and therefore their worth.

Science too is a source of lies and misdirections passed off as truth in order to maintain appearances of what is supposed to be irrefutable. The Lie Tree takes place amidst the chaos brought about by Darwin’s published tracts on evolution throwing into doubt the Holy Bible’s sanctity. Faith finds solace in the practice of science as an objective act rooted in research, observation, and logic. Yet the institution of science, under the guise of truth, condemns her as an abomination when Vane’s doctor assures Faith that women are intellectually inferior to men because of their smaller skull size:

[Faith] felt utterly crushed and betrayed. Science had betrayed her. She had always believed deep down that science would not judge her, even if people did. Her father’s books and opened to her touch easily enough. His journals had not flinched from her all too female gaze. But it seemed that science had weighed her, labeled her, and found her wanting. Science had decreed that she could not be clever … and that if by some miracle she was clever, it meant there was something terribly wrong with her.

Of course, the only reason science is a source of lies is because these lies must be told in order to maintain social appearances and social truths of how things supposedly work and men and women supposedly behave. In giving name and shape to these appearances, Frances Hardinge throws into relief how the social and scientific categories that define men and women’s identities and relationships, their social standings, and their reputations in life and in death are all constructed out of appearances, of what people believe or wish to be the truth rather than what actually is.

With regard to Faith Sunderly, she is a wonderful character, and I adore her. Largely ignored and looked down on by both her parents, Faith is torn between the desire to be the good, proper daughter she knows she should be, the visibly clever girl and scientist she wants to be, and the wicked girl she’s scared she’ll become. When Faith’s father was alive, all she craved was his validation that she was clever and that it wasn’t wrong of her to study science. After he is murdered, she dispenses with being nice and being good in favor of being cruel and vengeful in order to get the information and answers she needs.

Faith’s arc exemplifies all that is good in how Frances Hardinge explores societal and moral expectations of women, women’s roles, and women’s lived realities of lacking societal power and protection, and exploring them in a way that doesn’t make me want to gag: Women are as smart and capable and deserving of the same opportunities as men. They are also just as sly, vindictive, calculating, angry, deceitful, violent, selfish, and cruel. Most importantly, women can be all those things and simultaneously be clever and intelligent, and deserving of acknowledgement and admiration for their skills and talents. Women who are ostensibly shallow and vain, like Faith’s mother, turn out to be fighting as dirty and ruthless a game of their own in order to rip free any shred of control and independence of their future that they can, in the limited space society allows them to exist within.

(The villain of The Lie Tree—I should have figured out who it was. I’ve read Fly Trap, I know how Hardinge writes her stories, and even so I completely missed it.)

One of my absolute favorite things about Frances Hardinge is that her female characters are not paragons of virtue and morality, but neither does she write them such that they are “allowed” to have flaws. Faith Sunderly, just like Triss Crescent and Mosca Mye before her, finds her strength and comes into her own identity by breaking the rules and fighting dirty. They are neither good nor bad—they are good and bad.

Other things I loved—Faith’s grudging, untrusting alliance with the teenage boy Paul, son of Vane’s cleric and photographer. Not a friendship, and most definitely not a romance, their relationship is built on mutual loathing and spite, with each using the other for their own ends while unexpectedly developing a rapport over their mutual feelings of invisibility and distance within their own families.

And, of course, there’s Frances Hardinge’s writing. She makes me wish I was a far better writer myself, just so I could better describe how wonderful hers is. The Lie Tree is the least fantastical of her books that I’ve read so far, and strangely enough, it may be the better for it—Hardinge is a fantastic historical fiction writer in how she brings to life places and times, as well as characters of those places and times who are neither commendable or condemnable, but are their own characters. Yet even though this book less fantastical, Hardinge’s evocative imagination and skill with words imbues the story with an air of potential of the supernatural, the possibility that even the “real” world possesses far stranger things than may seem possible.

I want to end this review by quoting The Lie Tree—I can’t think of a better summation of this book than this:

“So what do you want?” asked Myrtle.

“I want to help evolution.”

Evolution did not fill Fait with the same horror her father had felt. Why should she weep to hear that nothing was set in stone? Everything could change. Everything could get better. Everything was getting better, inch by inch, so slowly that she could not see it, but knowing it gave her strength.

“My dearest girl, I have not the faintest idea what you are talking about.”

Faith thought about the best way to rephrase her resolution.

“I want to be a bad example,” she said.

“I see.” Myrtle stirred herself, ready to walk to the prow. “Well, my dear, I think you have made an excellent start.”

Pingback: My Favorite Reads of 2016 | Alive and Narrating